, my colleagues in children's literature are responding to Disney's presentation of P. L. Travers. In reading Jerry Griswold's '

I read that Travers had spent time on the Navajo reservation during WWII. In his

Collier---a name well known to us Pueblo people! Intrigued, I continued to read that interview. In it, she says that she liked the "wide, flounced Spanish skirts with little velvet jackets" that the Navajo women were wearing, and so, they made a skirt and jacket for her. Is there, I wonder, a photo of her in that skirt and jacket? For those of you who aren't familiar with these items, here's a board book with a child in that clothing:

In the interview, Travers also said "The Indians in the Pueblo tribe gave me an Indian name and they said I must never reveal it. Every Indian has a secret name as well as his public name. This moved me very much because I have a strong feeling about names, that names are part of a person, a very private thing to each one." Interesting! I have a Tewa (name of our language) name, but it is not secret. What pueblo, I wonder, did she visit? At the time of her visit, did that pueblo have secret names?

I've got lots of questions! I'll add them, and answers I find, in the coming hours and days. If you're a scholar of fan of Travers and can send me info about her time with Navajo and Pueblo people, please do!

Mary Poppins was published in 1934. Her visit to the Navajo Reservation was, I'm guessing, in the early 1940s. In

the Paris Review interview, she is described as wearing "silver ethnic" jewelry. In the BBC video

The Secret Life of Mary Poppins, there is a clip in which she is interviewed in 1982. I think she is wearing that jewelry in the interview:

That jewelry stood out in her granddaughter's memory. At the 50:00 mark of the documentary, Kitty remembers her grandmother "wearing all this extraordinary silver jewelry." At about that point in the documentary there is a clip of Travers at her typewriter. You can definitely see the jewelry is turquoise and silver. Whether it is Navajo or Pueblo in origin is hard to tell:

In the documentary, I learned that by 1959, Disney had spent 15 years trying to get the rights to make the movie. That means 1945, which fits with when she was in New Mexico and Arizona. Thus far, I haven't seen anything about why she was in the US at that time. Was it to meet with Disney?!

Next on my research exploration: reading Valerie Larson's biography,

Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The Life of P.L. Travers.

Before moving on to do that, I'm inserting a link to a short piece I did on Mary Poppins a couple of years ago:

"You Will Not Behave like a Red Indian, Michael!"

Update: Monday, January 6, 2014, at 12:20 PM CST

Yesterday afternoon and evening I read the parts of Larson's biography that are about Travers being in New Mexico. It was not, as I'd surmised, to visit Disney. The following notes are from my reading of Larson's biography (

Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The Life of P.L. Travers).

Travers was in the US due to the war.

In 1939, Travers adopted a baby boy named Camillus (in the BBC documentary, there's a lot of attention on the adoption. She didn't adopt his twin; when Camillus learned about his twin, he was 17. Until then, he'd thought he was born to Travers and that his father had died. Learning the truth caused problems between the two.) This was the period during the war in which people were leaving London for safer places.

In 1940, Travers left, too, on a ship that carried 300 children to Canada. She served as escort for some of the children. Once in Canada, she flew to New York City. She had women friends there: Jessie Orage and Gertrude Hermes. Jessie moved to Santa Fe soon after to be with "a community of Orage and

Gurdjieff followers." Prior to her move, she'd been very close to AE (Irish writer George William Russell), who knew John Collier (Larson calls him a 'minister' in Roosevelt's administration. Collier's position was actually Commissioner of Indian Affairs).

In the summer of 1941, Travers spent most of her time in Maine. In January of 1942, Jessie visited her in New York. "Gert" (Gertrude Hermes) and Travers separated that year. In 1943, her

Mary Poppins Opens the Door was published and she was feeling very homesick.

Collier suggested she spent a summer or two on an Indian reservation. At first resistant to the idea, Larson writes that Travers (note: the following excerpts are from Chapter 10 in the ebook w/o page numbers):

later felt Collier's offer came as a kind of magic. The next two summers were to be among the great experiences of her life. She moved from the gray reality of New York to the brilliantly colored fantasy of the southwest, just as Poppins moves through a mirage door from her earthly Cherry Tree Lane to her heavenly friends in the sky. Here, Pamela discovered what so many artists and writers had found before and after her: spiritual peace and meaning within a beautiful landscape, brittle, red, gray-green.

Her first visit was in September of 1943, to Santa Fe, where Jessie was living. Though she may have visited the Navajo reservation then, Larson makes no mention of it. That came later, in the summer of 1944, when Travers was in the southwest for five months. Larson writes:

She had accepted John Collier's suggest that she live for some weeks in Window Rock, a tiny Navajo settlement in Arizona, near the New Mexico border. It looked like a train stop at the end of the world.

And,

Pamela like to say she spent the summer on a reservation, but photographs in her albums show that she and Camillus lived in a western-style building that Pamela indicated in one interview was a boarding house. On the grounds in front, grinning for the camera, Camillus sat perched on the back of Silver, a white horse.

Larson writes that Travers was driven to the "reservations" (reservation is correct) where she tried to "speak little but hear much." During those storytelling sessions, Larson writes that Travers was "folding herself away so she did not seem to be listening to the Navajos' stories. She wanted to share the dances and songs, share the silence." (Note: I don't know what to make of that... perhaps she was trying to absorb what was happening around her in some metaphysical way.)

She also went to puberty ceremonies for Navajo girls and liked the matriarchal society. Larson writes:

Pamela took notes of the Navajo ways, religion, hierarchy, spiritual leaders: first the Holy Ones who can travel on a sunbeam or the wind, the Changing Woman, the earth mother who teaches people to live in harmony with nature, and her children, the Hero Twins, who keep enemies away.

She saw relationships between Navajo stories and those of other people around the world. She ate in hogans, and, wrote that Camillus:

"was taken by the hand by grave red men, gravely played with, and, ultimate honor, gravely given an Indian name. Its strange beautiful syllables mean "Son of the Aspen."

Travers was also given a name, but, Larson writes:

Pamela was given a secret Indian name and told "I must never reveal it and I have never told a soul." Her secret name, she said, "bound her to the mothering land," that is the land of the Earth Mother--her own motherland was far away.

Travers also went out to ceremonial dancing that took place at night. She rode blue jeans, boots, and cowboy shirts as she rode a horse in Canyon de Chelly. As noted above, she liked the skirts and jackets Navajo women wore. Larson writes:

From these days she adopted two fashions she wore until old age: tiered floral skirts and Indian jewelry, turquoise and silver, with bracelets stacked up each forearm like gauntlets.

Travers wrote to Jessie that was returning to Santa Fe. On July 19th, Jessie visited her in a Santa Fe hotel and drove her to the writer/artist colony in Taos. In September she helped Travers find a place to live in Santa Fe. In November, Travers returned to New York and in March, moved back to London. Larson refers to the bracelets a few additional times in the remainder of the book.

Next up? Some analysis and hard thinking about the ways that Travers depicted/incorporated Native content in her stories.

Update: Tuesday, January 7, 2014

Before the analysis, I'll take a few minutes to note that the documentary "PL Travers: The Real Mary Poppins" says that Disney was, in fact, in touch with Travers in 1944. At around the 2:00 mark of

this segment, you'll hear that Disney began negotiations with her in January. The documentary shows an inter-office communication dated January 24, 1944, with "Mary Poppin Stories" as the subject. There's a second item--a letter to Travers--dated February 1944 at around 2:10 in the documentary. It references Travers plan to visit Arizona and suggests a meeting. If you're interested in Travers and her relationship with Disney as they developed the script and movie, watch the video. It has screen shots of letters she wrote, and audio clips, in which she objected to aspects of the script.

In part 4 of that documentary, one of her friends talks about how Travers studied dance of other cultures because that was a way they told stories. At 4:51, the person who did choreography for the Disney film speculates that her interest in dance is evident in her stories, where dance and flying figures prominently. At 4:51 in the segment, there's a video clip of an Eagle Dance! It is a Pueblo dance, not a Navajo one. The choreographer talks about her lectures and then the segment goes to an audio recording of her from a talk she gave at Smith College in 1966 in which she says:

When I was in Arizona living with the Indians for two summers during the war, they gave me an Indian name and they said 'we give you this so that you will never never tell it to anybody. Anybody can know your other name but this name must never be spoken' and I've never spoke of it from that day to this. There is something very strange and mysterious about ones names. I myself always tremble when people I don't know very well take my Christian name. I tremble inside. I don't like it.

All through that audio, there are clips of the eagle dance. Are those clips from her own footage? I recognize the Eagle Dance, and I recognize Taos Pueblo, too.

Patricia Feltman, her friend, says that Travers spent two summers with the Navajo Indians, who made the jewelry she wore every day of her life.

That's it for now.... More later.

Update: Wednesday, January 8, 2013, 1:57 PM CST

Of interest to me is the ways in which Travers wrote about what is generally called "other." This happens in the Bad Tuesday chapter in the first book, published in 1934. It was turned into a

Little Golden Book in 1953. Here's screen captures of two pages in the part of the book (I don't have the book myself) in which Mary Poppins and the children go West using the compass. The source for my screen captures is

kewzoo's account at flickr.

As yet, I don't have the original book to compare the words in it to the words in the Little Golden Book above. I don't find any of that text in the 2007 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt copy that I'm reading. Those pages in which they travel using the compass were completely rewritten. As she says below in the interview, she kept the plot (of traveling) but apparently changed the people they met to animals. In the revised chapter, when they're in the West, they see dolphins, not Indians. That this is a revised chapter is clearly marked in the Table of Contents:

I turn now, to two of Travers' responses to objections. The first one was published in 1977, and the second one in 1982.

Travers granted an interview to Albert V. Schwartz, who was at the time of the interview, an Assistant Professor of Language Arts at Richmond College in State Island. His account is available in

Cultural Conformity in Books for Children, edited by Donnarae MacCann and Gloria Woodard, published by Scarerow Press in 1977

.

When Schwartz learned that the chapter had been revised, he got in touch with the publisher, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich for details. He learned that the revisions took place in the 1972 paperback, at Travers' request. Schwartz then got in touch with Travers and set up the interview. He told her that the Council on Interracial Books for Children had been receiving complaints about stereotypical presentations of Africans, Chinese, Eskimos, and American Indians. Here's a quote from Schwartz's chapter (p. 135):

Sitting tall and tense, Pamela Travers was aware of every word as she spoke: "Remember Mary Poppins was written a long time ago when racism was not as important. About two years ago, a schoolteacher friend of mine, who is a devotee of Mary Poppins and reads it constantly to her class, told me that when she came to that part it always made her squirm if she had Black children in her class. I decided that if that should happen, if even one Black child were troubled, or even if she were troubled, then I would have to alter it. And so I altered the conversation part of it. I didn't alter the plot of the story. When the next edition, which was the paperback, came out, I also altered one of two things which had nothing to do with 'picaninny' talk at all.

"Various friends of mine, artists and writers, said to me, 'No, no! What you have written you have written. Stand by it!' But, I thought, no, if the least of these little ones is going to be hurt, I am going to alter it!"

A few paragraphs later is this:

"I am not really convinced that any harm is done," she continued. "I remember when I was first invited to New York by a group of schoolteachers and librarians, amongst whom were many Black teachers. We met at the New York Public Library. I had thought that they expected me to talk to them, but no, on the contrary, they wanted to thank me for writing Mary Poppins because it had been so popular with their classes. Not one of them took the opportunity--if indeed they noticed it--to talk about what you've mentioned in 'Bad Tuesday.'"

In his

1982 interview with Travers that is in the Paris Review, interviewers Edwina Burness and Jerry Griswold asked her about the book being removed from children's shelves in San Francisco libraries because of charges that the book is racist and that it has unflattering views of minorities. She said:

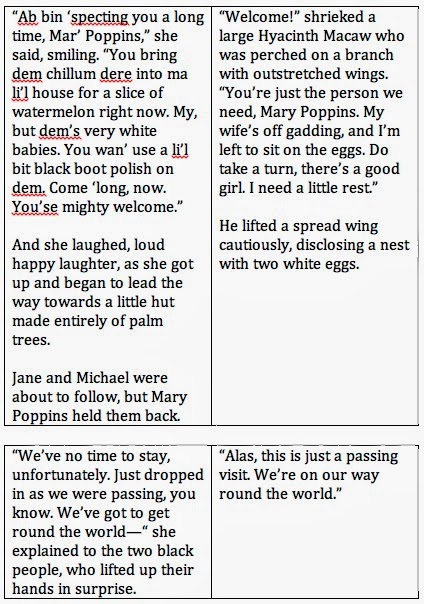

The Irish have an expression: “Ah, my grief!” It means “the pity of things.” The objections had been made to the chapter “Bad Tuesday,” where Mary Poppins goes to the four points of the compass. She meets a mandarin in the East, an Indian in the West, an Eskimo in the North, and blacks in the South who speak in a pickaninny language. What I find strange is that, while my critics claim to have children’s best interests in mind, children themselves have never objected to the book. In fact, they love it. That was certainly the case when I was asked to speak to an affectionate crowd of children at a library in Port of Spain in Trinidad. On another occasion, when a white teacher friend of mine explained how she felt uncomfortable reading the pickaninny dialect to her young students, I asked her, “And are the black children affronted?” “Not at all,” she replied, “it appeared they loved it.” Minorities is not a word in my vocabulary. And I wonder, sometimes, how much disservice is done children by some individuals who occasionally offer, with good intentions, to serve as their spokesmen. Nonetheless, I have rewritten the offending chapter, and in the revised edition I have substituted a panda, dolphin, polar bear, and macaw. I have done so not as an apology for anything I have written. The reason is much more simple: I do not wish to see Mary Poppins tucked away in the closet.

Interesting, isn't it? I'm still reading and thinking and will share more later. If you have other items to point me to, please do! And for those who have already done so, thank you!

Update: Thursday, January 9, 12:58 PM CST

Editors note, Jan 10, 2014, 5:26 PM CST --- the excepts described herein as 'original' are from a 1963 edition published by HBJ, prior to the revisions. From K.T. Horning, I've just learned that there were TWO revisions. In the first one, the human characters remained but the Black dialect was changed to what Travers described as "Proper English." I do not have a copy of "Bad Tuesday" that K.T. Horning referenced (in a comment on Facebook). If you do have that copy, please scan and send to me if you can!

Thanks to librarians, I now have the original chapter. Specifically, thank you, Michelle Willis! Michelle sent me the color scan of the compass and the chapter from which I created the side-by-side excerpts.

First up is the Mary Shepherd's illustration of the compass (illustrations for later versions were changed to match the changes to the text):

At the start of the Bad Tuesday chapter, Michael has gotten up on the wrong side of the bed. He's doing naughty things. Later in the day, Mary Poppins has taken Jane and Michael out for a walk. Mary Poppins sees the compass on the ground and tells Michael to pick it up. He wonders what it is, and she tells him it is for going around the world. Michael is skeptical, so Mary Poppins set out to prove to him that the compass can, indeed, take them around the world.

She begins their trip by saying "North!" The air starts to get very cold and the kids close their eyes. When they open them, they're surrounded by boulders of blue ice. Jane asks what has happened to them. (Below is the complete text from both versions for this section of the book. Blank boxes mean there was no corresponding text in the revision.) Here's an enlargement of the illustration for North:

|

| Enlargement of Eskimo, illustration by Mary Shepherd |

Next update? The South!

Update: Thursday, January 9, 2014, 2:25 PM CST

(I apologize for different size of the side-by-side images. I'm entering the text into a table in Word and then doing a screen capture according to the size of the boxes. It is clumsy, but it is the only way I know of for getting the text aligned side-by-side in Blogger.) An enlargement of "South" on the compass is followed by text:

|

| Enlargement of Mary Shepherd's illustration for South |

Here's the illustration for East, followed by the text:

|

Mary Shepherd's illustration of East

|

That's it for now. My next update will be West.

Update: Friday, January 10, 2014, 4:12 PM CST

Here's an enlargement of West on the compass:

|

| Mary Shepherd's illustration of West |

And here's the side-by-side comparisons of the original and revised versions of the portion of the book about West:

After that they head back home. As the afternoon wore on, Michael got naughtier and naughtier. Mary Poppins sent him to bed. Just as he climbed into bed he saw the compass on the chest of drawers and brought it into bed with him, thinking he would travel the world himself. He says "North, South, Eaast, West!" and then...

Then he hears Mary Poppins telling him calmly, "All right, all right. I'm not deaf, I'm thankful to say--no need to shout." He realizes the soft thing is his own blanket. Mary Poppins gets him some warm milk. He sips it slowly. The chapter ends with Michael saying "Isn't it a funny thing, Mary Poppins," he said drowsily. "I've been so very naughty and I feel so very good." Mary Poppins replies "Humph!" and then tucks him in and goes off to wash dishes.

MY INITIAL THOUGHTS

As the interviews above suggest, Travers made changes, but why? The two interviews differ in her reaction to objections. As far as I've been able to determine, the objections were to her portrayal of Blacks, but if you've seen articles or book chapters that described objections to the other content, do let me know!

The book was written before her trip to the southwest. It seems to me that if she had understood the significance of names (as she says in the interviews), she would have--on her own--revisited the names she gave to the Indians in the West, and she would have come away (after seeing dances) knowing that her depictions of dance were inappropriate. If she'd have been paying attention to the Navajo people (and Pueblo people, if she did indeed visit a Pueblo) as people rather than people-who-tell-stories-and-make-jewelry-and-dance, she would have--all on her own--rewritten that portion of the chapter. She didn't do that, however, until much later.

For now, I think I'll let things simmer and then post some analysis and concluding thoughts later.

In the meantime, submit comments here (or on Facebook). I'd love to hear what you think of all this.